Shifting the Flow

Alberta native trout have been threatened for years, but recent conservation efforts are supporting them and other at-risk species

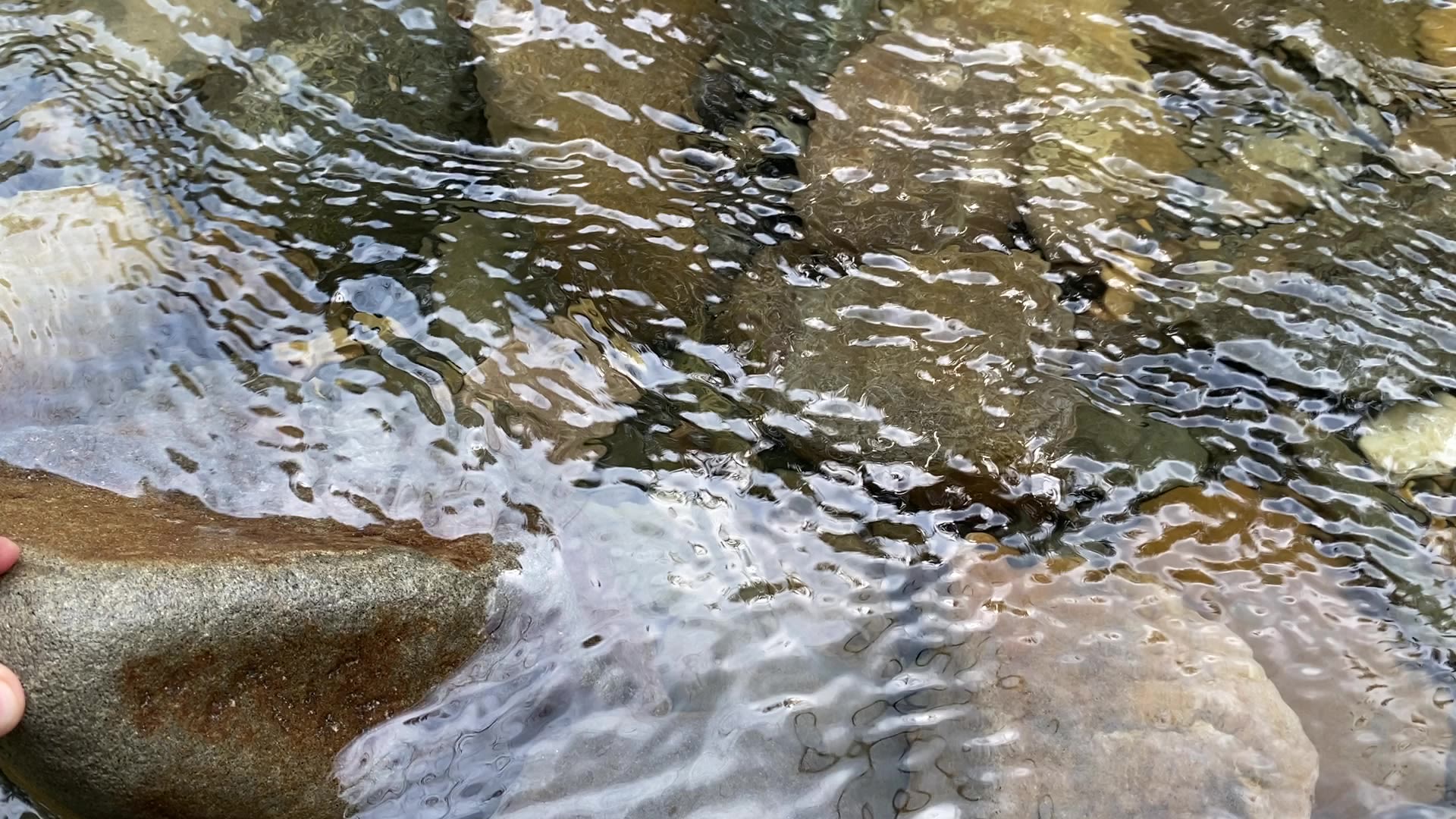

Cool, crystal water rushes over smooth stones, fed by glacial melt from the Rocky Mountains that have defined Alberta’s Eastern Slopes for centuries. The surrounding pine trees and tall grasses diffuse the sunlight, producing shimmering pockets of glare as light refracts off the water’s surface.

Suddenly, a flash of colour flickers beneath the surface — a westslope cutthroat trout, its silver body and pink underbelly wriggling against the river’s current.

Watching it make its way upstream, it’s easy to forget how little of the population is left.

The Eastern Slopes is one of the few remaining strongholds for Alberta native trout, and even its pristine waters are no longer a guaranteed safe haven. A variety of human and climate-related factors are jeopardizing the trout’s future.

But the loss of native trout has consequences beyond the immediate decline in populations. Trout act as an important indicator species for the ecosystems and headwaters they inhabit.

Their loss means the degradation of these areas, some of which supply 90 per cent of the drinking water for the communities and watersheds the Eastern Slopes feeds.

PART 1:

The Issue

Alberta’s native trout have been in trouble for years. Here’s why

What’s the problem?

Alberta is home to over 65 fish species, but when it comes to trout native to the province, the “Big Three” — westslope cutthroat trout, bull trout and Athabasca rainbow trout — are some of the most threatened. All are listed as at-risk species under Alberta’s Wildlife Act and the federal Species at Risk Act.

According to the Government of Alberta, these species were once abundant in the watersheds of the Eastern Slopes, but in recent years populations and their distribution has severely declined.

For the past decade, recovery strategies, proposals and grants, and both federal and provincial acts have been used to hopefully reverse these trout’s fates.

One of these, the Native Trout Recovery Program, seeks to align provincial government ministries and departments with conservation groups and biologists in a “long-term fish conservation initiative aimed at assessing, recovering and monitoring” native trout populations, starting with the Eastern Slopes.

In a statement, Minister of Environment and Protected Areas Rebecca Schulz said the government is “working with experts and conservation groups across Alberta to keep Native Trout and other at-risk species from disappearing.”

“Since 2019, Alberta’s Native Trout Recovery Program has restored 112,000 square meters of aquatic habitat and are helping support a variety of species, including the Athabasca rainbow trout, bull trout and Westslope cutthroat trout,” she said, adding the 2025 budget will allocate $400,000 to expand trout recovery projects if passed.

Indicators of their environment

Native trout, specifically bull trout, are known to be important indicator species for their environments, says Christie Sampson, an assistant professor of biology at the University of the Ozarks in Arkansas, U.S.

“Bull trout are excellent at that because they are pretty particular in how they like to live or how the conditions with which, under which they can thrive and survive,” she says.

Since native trout need specific aquatic conditions to survive, the fish can often tell researchers a lot about the health of the surrounding environment, says Sampson.

“Just by their presence there, then we know that, for example, the water is cold enough for them to survive or it's clean enough for them to survive,” she says. “If you're not seeing those things, or you're not seeing the fish, then you know something's going wrong in the habitat.”

Indicator species are also important harbingers of climate change. Sampson says bull trout can demonstrate the effects of rising global temperatures at a local level.

“As the waters warm, bull trout being cold water species can't really survive there anymore and so they'll get pushed out,” she says.

Cumulative Effects

Understanding exactly what has caused the decline of these species, however, remains difficult. The province’s recovery program has identified over 20 human-related threats to the three species. Bull trout experts found over 16 threats for that species alone that were tied to some sort of human activity.

“It isn’t just one thing,” says Bob Weir, a member and past president of the Calgary Fish and Game Association.

Still, the recovery program has organized the main threats into three categories — habitat degradation and destruction, illegal harvesting and improper catch and release methods and hybridization, or breeding with non-native or other native trout species.

When it comes to finding a clear culprit for the decline in these trout populations, there is no one clear activity.

No one thing has negatively impacted the trout populations. Cumulative effects are a collection of activities that have been recognized as harmful such as motor vehicle activity, forestry, climate change, mining and coal activity, livestock locations and hybridization. PHOTO BY: ALEX JANZ

No one thing has negatively impacted the trout populations. Cumulative effects are a collection of activities that have been recognized as harmful such as motor vehicle activity, forestry, climate change, mining and coal activity, livestock locations and hybridization. PHOTO BY: ALEX JANZ

Any and all action around the Eastern Slopes can be part of the problem, and this is known as cumulative effects.

According to the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), Alberta native trout require cold, clean, clear and connected waterways. Activities such as forestry, logging, mining and livestock activity, can damage existing watersheds and introduce sediment and other debris into the water.

“These native trout are sensitive to water temperatures and quality, compared to the non-native species,” says Weir.

But it’s not just industries. Everyday recreational activities also play a role in the endangerment of these trout and their habitat. Increasing amounts of ATV and fishing activity also disrupt the landscape.

Since COVID-19, Weir, an avid fisher and outdoorsman has noticed a boom in outdoor activity. My Wild Alberta reports in 2019 there were 248,458 resident sport fishing licenses. In 2020 it jumped to 322,492 licenses. Weir says the Eastern Slopes are one of the most accessible and popular places for sport fishers in the province, so naturally the area was subject to a major increase in recreational activity around that time.

Weir says even if these new fishers are practicing capture and release methods, they are lacking the proper knowledge on how to handle a fish. These incidents, while small, could lead to the death of a threatened trout.

All of these challenges make it all the more difficult for these fish populations to thrive–let alone survive. They can’t live just anywhere, and their habitat continues to be worn down.

Threats from hybridization

Not only are trout species experiencing loss of livable habitat, but there is a new threat — hybridization.

Hybridization is when two species are compatible enough to breed together. This cross breeding is quite prevalent between bull and brown trout, and rainbow and cutthroat. Most of the time, this mix of species means the offspring are born weak and can’t survive the same as a purebred trout.

Photo of a Cutbow, a hybrid species made when Athabasca Rainbow and Westslope Cutthroat trout cross breed. PHOTO BY: Inaturalist

Photo of a Cutbow, a hybrid species made when Athabasca Rainbow and Westslope Cutthroat trout cross breed. PHOTO BY: Inaturalist

Sampson is worried because it leads to the loss of genetically intact populations.

“Instead of having bull trout reproducing, creating more of their species, you're getting this hybrid that's not healthy, not really good for the ecosystem,” says Sampson

Hybridization is not always a bad thing, and sometimes can be one way for a species' genetics to carry on while the original species population shrinks.

As the provincial fish, bull trout are beloved by anglers for their feisty spirit. Losing them would not only be a loss of provincial identity, but damage the ecosystems they support.

Sampson explains the genetics of the bull trout will begin to fade the more they cross breed. The jobs they do that no other species can, like keeping bug populations balanced by eating them, will take a toll on the environment.

“They won't be serving the same roles that they did previously, and that can be a big issue,” says Sampson.

The link between trout and drinking water

Joshua Killeen, conversation science and programs manager at CPAWS, notes that the issue of water availability and quality is becoming increasingly salient in the minds of southern Albertans, all of whom use water that flows from the Eastern Slopes.

“That’s the water that people drink. That’s the water that irrigates our farmland. You can be sure that if the native trout are not doing well in a watershed, then that’s indicative of problems in water quality. There’s a very close connection between that availability of water and those species,” he said.

Killeen says that Albertans’ concerns over the water that flows from their taps might bring them closer to understanding that water quality in the province's watersheds and declining trout populations are inexorably linked.

Anglers have an up-close and personal relationship with these trout. Weir has been frequenting the Eastern Slopes for decades and has noticed a drastic change in the trout populations.

Weir says the angler community finds hybridization and invasive species to be two of their biggest grievances. Weir notes the fish are smaller, and a lot look unhealthier when he pulls them in for a catch and release.

Steps towards recovery

Since these species have been protected under Canada's federal Species at Risk Act, the provincial government is expected to change the fate of these important indicator species.

In 2019, almost a decade after these three fish were showing signs of population decline, a collaborative of organizations dedicated to reversing the problem emerged.

The Alberta Native Trout Collaborative is made up of several smaller organizations, such as Cows and Fish, fRI Research, CPAWS and Freshwater Conservation Canada. Funded by the government of Canada’s nature legacy grant, they work in partnership with the Government of Alberta to develop data driven research, educational tools and hands-on projects.

Collaboration between these groups means they are able to share research and avoid overlap in restoration efforts. Each brings unique expertise in different areas of data collection, data interpretation and research, habitat restoration, communication and education.

PART 2:

Saving the Trout

Little fish in a big issue

Native trout are not yet lost to the Eastern slopes, but they are incapable of helping themselves.

The Alberta Trout Collaborative combines multiple organizations, corporations and charities that share the hope that these trout can re-populate. Working in partnership with the Government of Alberta, the trout collaborative works in diverse areas to help the trout like research, recovery projects, communications and public education initiatives.

These groups operate with the belief that their work will lead to a better understanding of how to protect trout populations, which in turn will benefit the surrounding ecosystem.

Belief alone does not make the world go round however, and the collaborative is constantly fighting for funding.

The Species at Risk Act is a federal government act. If a species is declared endangered then it must be protected. A provincial government leader is appointed to head up the act and they are obligated to create an action plan that will manage and monitor the species. This action plan takes into account research, conservation and education.

However, the Species at Risk Act provides almost no funding to actually solve any problems. The longer the collaborative waits for funding, the more population loss the trout experience.

Like a ticking ecological time bomb

Critical habitat

Critical habitat is the measured amount of habitat designated for a protected species, under the species at risk act.

Bull, Athabasca rainbow and cutthroat trout are quite picky when it comes to their homes. Their critical habitat is described as “cold, clean, complex and connected” by CPAWS, a member of the Alberta Native Trout Collaborative.

Under the Species at Risk Act, it is illegal to damage or infringe on the designated Critical Habitat. However, Joshua Killeen conservation science and programs manager at CPAWS says the legislation does not prevent habitat loss.

“We have the definition and it is legally protected, and yet on the ground we are seeing critical habitat loss take place regularly across the region,” says Killeen.

Killeen offers a bleak observation of the critical habitat of the bull, rainbow and cutthroat trout, saying they’re facing “an alarming loss of habitat.”

In part the loss is due to cumulative effects and the very slow processes of government. Killeen explains that since 2008 when trout were protected under the Species at Risk Act, seven regions of Alberta were supposed to have recovery plans in place.

Almost two decades later and only two regions have passed protection plans.

Hitting a wall at every turn, Killeen says “it’s been tough to maintain action,” on trout recovery.

Research projects

A big piece of native trout recovery is just learning more about them. fRI Research does exactly what their name suggests—research.

The extensive knowledge they gain about these trout species through research can then hopefully be used to better inform recovery projects—once funding and government approval is secured.

Benjamin Kissinger is the program lead for the water and fish program at fRI Research. He says the organization works closely with masters students and postdoctoral students to complete many different kinds of research.

Genetics research is similar to studying the fingerprint of the different trout species. The tool is used to better understand how trout species are related to one another. Kissinger says hybridization is “identified as one of the top issues for persistence of that species,” (Athabasca Rainbow and Westslope Cutthroat).

A recent genetic research project investigated the location of populations of cutthroat trout and the difference in their genetics based on their location.

When applied, this research could be used to take population from one location and establish it in another, by being able to predict which group might fit best in the new location.

"Because we're a not-for-profit, we can’t do this ourselves. The province would have to have approvals in place to be able to implement it."

Another research project completed with assistance from fRI and a masters student looked specifically at bull trout. The project planted chambers of bull eggs into Smith Dorrien Creek, a well known bull trout spawning location. A success, it was proven that bull trout could be hatched from these chambers. This research could be used to spawn bull trout, reestablishing them back into areas where they historically lived, or a new area they’ve never existed before.

Once the research is complete, without funding they can always count on, little can be done to move forwards with recovery projects.

“Because we're a not-for-profit, we can’t do this ourselves. The province would have to have approvals in place to be able to implement it,” says Kissinger.

Lack of funding once again being a hurdle in the way of trout regaining their livelihood.

Smith Dorrien Trail, Alta. fRI Research and a team of masters students have been working on planting chambers of bull trout eggs into Smith Dorrien Creek to help populations recover. PHOTO BY: SIMPF/FLICKR

Smith Dorrien Trail, Alta. fRI Research and a team of masters students have been working on planting chambers of bull trout eggs into Smith Dorrien Creek to help populations recover. PHOTO BY: SIMPF/FLICKR

Where the money flows

However, Kissinger explains there is a stream of income for these research projects and recovery projects coming from an unlikely source, Alberta’s forestry industry. fRI Research receives funding from Alberta Forestry and Parks and varying monetary support from Alberta Parks and Environment. This is partly because Alberta Parks and Environment is so small themselves they don’t have much funding to spread around.

Logging and development activity around critical habitats means something has to be done to offset the impact. Forestry companies have a portion of their profits automatically deposited into the forest resource improvement program, managed by Forest Resource Improvement Association of Alberta (FRIAA).

“From a funding standpoint provincially there's almost no funding support. Any of the dollars that have come in for us [from Alberta Environment and protected areas] to do this have been from the feds or industry partners,” says Kissinger.

Industry partners are forestry companies that give money to programs like FRIAA. This fund is used to ensure responsible forestry management and resource sustainability in Alberta.

“Putting those dollars back into projects that could help recover fish species would be in their best interest since it’s currently impacting their processes on the landscape,” says Kissinger.

Logging and development activity around critical habitats means something has to be done to offset the impact. Organizations like the Forest Resource Improvement Association of Alberta work to restore forests, which also support healthy habitats for trout. PHOTO BY: RYAN BEIRNE/PEXELS

Logging and development activity around critical habitats means something has to be done to offset the impact. Organizations like the Forest Resource Improvement Association of Alberta work to restore forests, which also support healthy habitats for trout. PHOTO BY: RYAN BEIRNE/PEXELS

Application of this research isn't as straightforward as putting a chamber of bull trout eggs into a river.

There's a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes of a recovery project, namely and most importantly all the different research that needs to be done first. Multiple different research projects and academic theses and publications could be used for just one recovery project.

Once the project is underway, permits are needed, and assessments of disease and genetics need to be done. Then, the fish’s survival in the location has to be assessed. Of course, a team with both the knowledge and skill needs to be organized to execute the project. Following all of that, monitoring of the species in its new habitat has to be done for five years afterwards. This monitoring is key, as it indicates whether the trout population is actually reestablished in a new location or not.

None of this process can be done without financial support.

FRIAA’s fund supplements some of the costs, and AEPA some of the labour. But trout aren’t the only animal in Alberta that needs help, and resources are divided up among many different projects. So much more work could be done for the trout, more efficiently if there were governmentally supplied funding in place.

“Having dedicated long term funding from the province or the feds would be huge,” says Kissinger.

PART 3:

Beyond Trout

Amid efforts to save native trout, Alberta’s amphibians are also struggling

When picturing the species of a river or stream, most people think of fish first. Unless of course they’re Kris Kendell, who has always been fascinated with the less obvious amphibians inhabiting the water’s shorelines.

“As a kid I would be out in nature and I would hear some noise coming from a wetland and I would naturally want to explore it,” he says.

Amphibians, which includes frogs, toads and salamanders, are typically harder to see than fish, especially while they hibernate in the winter months. For Kendall, their near invisibility is what makes them so unique.

“Over the winter as a kid, when I did encounter them, it would always be something special because it wasn't like they were always around and they took some searching for,” he recalls.

When they finally did emerge in the spring, Kendall says their choruses during the mating season were always a sign warmer weather was coming.

This aerial shot shows part of the Battle River, which runs through Alberta and Saskatchewan. It is a vital habitat for various species in east-central Alberta. PHOTO BY: COWS AND FISH

This aerial shot shows part of the Battle River, which runs through Alberta and Saskatchewan. It is a vital habitat for various species in east-central Alberta. PHOTO BY: COWS AND FISH

While Alberta native trout and amphibians usually have very little in common, like trout, amphibians are important indicator species for their environment and are also facing increased threats from habitat loss, pollution and disease.

On top of all that, efforts to stock ponds and wetlands for fishing with both native and non-native trout species can also harm amphibian populations, prompting biologists and advocates to call for deeper consideration of the complex interactions between amphibians and trout in conservation work to preserve both species.

Monitoring a challenge amid population threats

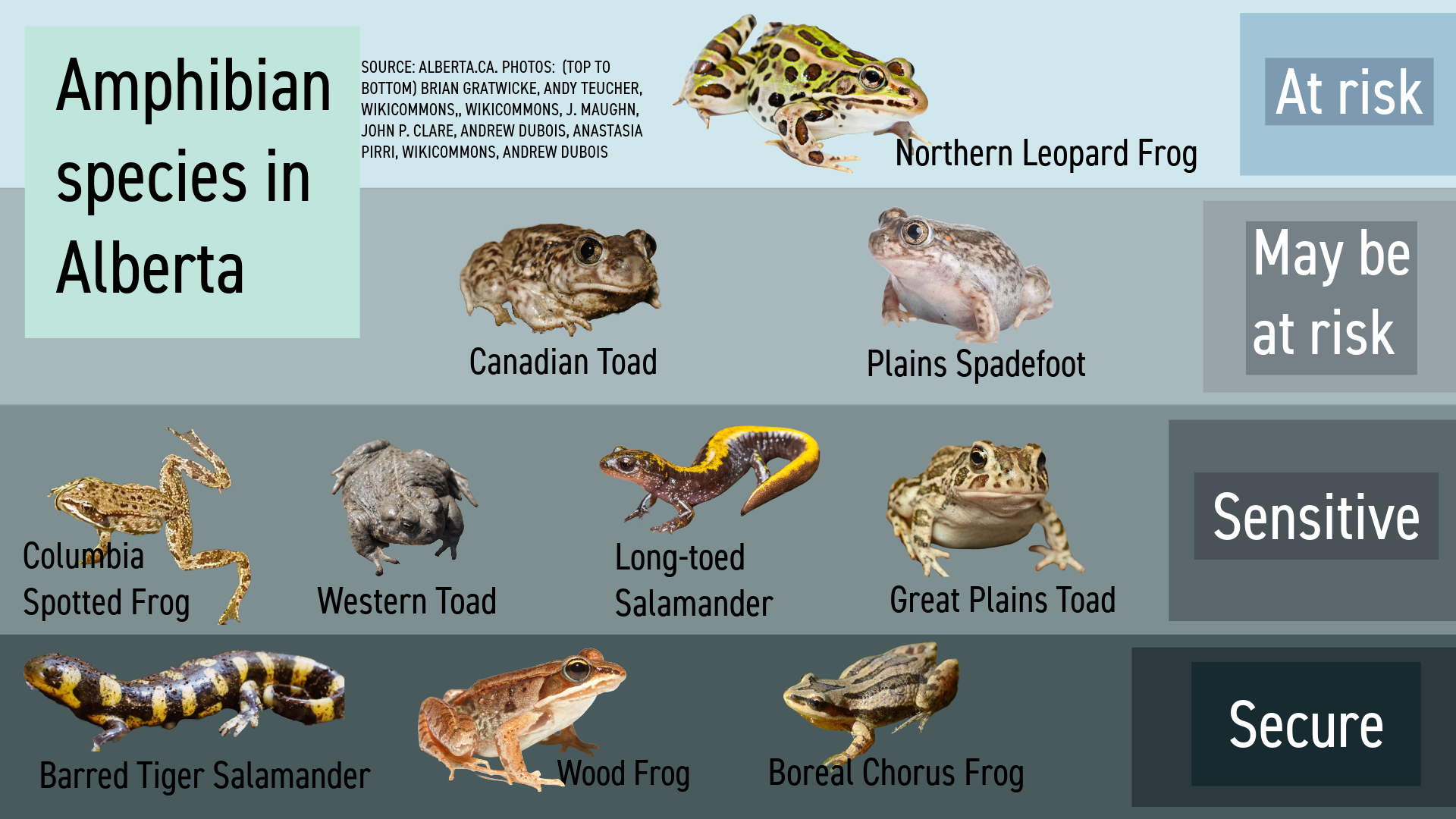

Alberta has 10 amphibian species — two salamander species and eight types of frogs and toads. Of these, only three are considered secure, while the rest are either ranked as ‘sensitive,’ ‘may be at risk’ or ‘at risk’ under the province’s general status rankings.

According to Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, 56 per cent of Alberta’s frogs are endangered, representing the second-highest behind British Columbia.

The seven species who are of conservation concern are largely found in the southern portion of the province, says Cynthia Paszkowski, a professor emerita at the University of Alberta.

She says this is because there are more species in the south and they tend to be habitat specialists, meaning they can only survive in very specific conditions.

This chart illustrates the general status of Alberta's 10 amphibian species. IMAGE BY: STEPHANIE GABRIEL

This chart illustrates the general status of Alberta's 10 amphibian species. IMAGE BY: STEPHANIE GABRIEL

But unlike other, more visible species, exact population numbers of amphibians are unknown. Paszkowski says this is due in part to the sheer number of wetlands and waterbodies across the province, with many being difficult for researchers to get to.

“Many of them in the northern part of the province are very inaccessible and likewise in the mountains,” she says, adding prairie wetlands can be remote too.

“It's difficult to keep your pulse on that when you have so many different localities,” she says.

Additionally, monitoring species based on breeding activity can be problematic as many species do not breed regularly, especially if the conditions are unfavourable.

Alberta has two types of salamander, including the long-toed salamander. They have no breeding calls and are rarely seen above ground, making them tough to spot. PHOTO BY: OREGON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE/FLICKR

Alberta has two types of salamander, including the long-toed salamander. They have no breeding calls and are rarely seen above ground, making them tough to spot. PHOTO BY: OREGON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE/FLICKR

Paskowski says this can give the impression there are no amphibian species, when in reality they’re just inactive.

Kendall, who is a wildlife biologist with the Alberta Conservation Association (ACA), agrees, adding species will fluctuate depending on if the weather is hot and dry, or rainy and wet.

“It's a bit subjective because during dry-hot conditions, amphibians may switch their activity to being more at night, or they may be more undercover to escape unfavorable conditions,” he says. “There could be lots of them, but we just don't notice them.”

Unwanted mixing and mingling

The relationship between native trout and amphibians can be intricate at best.

On the one hand, all of the amphibian species in Alberta spend most of their time in moist, terrestrial areas after hatching and maturing in water. Any water they do inhabit, is shallow, and warm — the exact opposite of the deep, cool water trout prefer.

Alberta's amphibians require three main habitat requirements: a place to breed, to forage and to overwinter. They also require safe movement between these habitats, which can be disrupted by construction projects or roadways. IMAGE BY: KELSEA ARNETT

Alberta's amphibians require three main habitat requirements: a place to breed, to forage and to overwinter. They also require safe movement between these habitats, which can be disrupted by construction projects or roadways. IMAGE BY: KELSEA ARNETT

Paszkowski, however, says there are instances where trout and amphibians may come into contact, such as in headwaters both species have historically lived in, or, in more insidious instances, where ponds have been stocked with trout for fishing.

Trout do not typically eat amphibians or their tadpoles and larvae, instead preferring large invertebrates and smaller fish. In rare cases, they may prey on frog species like the northern leopard frog, who hibernate at the bottom of streams.

Northern leopard frogs hibernate at the bottom of streams. Out of all Alberta's amphibians they have the highest general status of 'at risk.' PHOTO BY: KRIS KENDELL

Northern leopard frogs hibernate at the bottom of streams. Out of all Alberta's amphibians they have the highest general status of 'at risk.' PHOTO BY: KRIS KENDELL

“They're completely inert, lying at the bottom of a slow-flowing stream, and they breathe through their skin,” Paszkowski says. “Now this would be a situation where potentially a trout, say maybe rainbow trout, could come in contact with an amphibian in winter when the amphibian is basically knocked out … and could eat them.”

Stocking trout in an area they would already be isn’t a problem, Paszkowski says. The main issues occur when it’s assumed native trout are native to every waterbody in the province.

“If it's not a very productive system, the trout are going to pretty much have to eat whatever they find there,” she says, adding this means tadpoles and larvae.

But in a more productive environment, meaning the trout have enough food sources, Paszkowski says they can actually help by eating large invertebrates who prey on amphibians’ offspring.

‘Canaries in the coal mine’

While native trout and amphibians have different environmental needs, both provide important signs of an ecosystem’s health.

Referring to them as the “canaries in the coal mine,” Kendall says amphibians are important indicator species for their environment, and can tell scientists a lot about both land and water.

“They can tell us the health of their aquatic systems because part of their life cycle is in aquatic systems, and then also part of their life cycle is on land, so they can also tell us how their land is doing,” he says.

The boreal chorus frog has a loud and distinctive breeding call, but because of its small size and ability to camouflage easily it is often overlooked. PHOTO BY: KRIS KENDELL

The boreal chorus frog has a loud and distinctive breeding call, but because of its small size and ability to camouflage easily it is often overlooked. PHOTO BY: KRIS KENDELL

Amphibians also breathe through their thin, permeable skin, meaning they can also easily absorb chemicals and other contaminants, telling biologists about the quality of the environment.

Similar to native trout, Kendall says amphibians also need healthy riparian zones to act as buffers for chemical run-off and provide hibernation locations. Conserving these areas for native trout can also benefit amphibian populations.

“Those buffers along these water bodies can serve the fish very well, and that's also where amphibians are breeding,” he says. “They all benefit from that riparian habitat.”

Where do we go from here?

Although the monitoring of amphibian species remains a challenge, Paszkowski says biologists’ knowledge of amphibians has improved significantly over the past 30 years.

New technology such as environmental DNA — which involves collecting water samples and then testing them for different species’ DNA — can allow scientists to examine whether an amphibian species is in an area without physically seeing them.

Efforts such as the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute’s autonomous recording units allow scientists to record frog and toad calls to measure the distribution of a particular species. While Paszkowski says this technology is still not a great measure of population numbers, it does allow scientists to monitor frog and toad presence in remote wetlands.

The ACA’s Alberta Volunteer Amphibian Monitoring Program is another example of a program aimed at getting more eyes and ears looking for amphibians. Kendall says the citizen science program encourages anyone to share their observations of amphibians and reptiles through a form. The data is then shared with the government to better understand the species’ distribution.

But aside from the information benefits, Kendall hopes people come to appreciate amphibian species as much as more identifiable ones.

“Once people appreciate amphibians and understand their contribution to our ecosystems and how they enrich our lives … then we can start to think about stewardship and how we can benefit these creatures,” he says.

“Once people appreciate amphibians and understand their contribution to our ecosystems and how they enrich our lives … then we can start to think about stewardship and how we can benefit these creatures”

PART FOUR:

A Path Forward

The future of fish in Alberta

When looking forward, many people involved in Alberta’s trout repopulation efforts share one main concern: funding.

“Grant funding is drying up a little bit,” says Angela Ten, biologist at Freshwater Conservation Canada (formerly Trout Unlimited Canada). “We’re unsure about how it’s going to look moving forward.”

As part of the Alberta Native Trout Collaborative, Ten says that her organization competes for funding not only with other organizations in the Collaborative, but with new restoration groups that are popping up to help tackle the issue.

And as Freshwater’s current funding through the Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (from Fishers and Oceans Canada) ends at the end of March 2026, she notes that there will be even less money on the table for all these groups.

“It can be pretty frustrating at times but it passes quickly,” she says.

With many different projects running concurrently, and many more in their planning stages, Ten says that even when bureaucratic or funding issues impede their progress in one area, usually they can look to the success of their work in another area to keep a positive attitude.

Most projects take two to five years to complete – practicing patience is a necessity in her line of work. “We know that if we keep at it, we’ll do it eventually.”

A collaboration between Freshwater Conservation Canada and Calgary-based Leaf Ninjas to work on conservation efforts in Elk Creek. PHOTO BY: FRESHWATER CANADA

A collaboration between Freshwater Conservation Canada and Calgary-based Leaf Ninjas to work on conservation efforts in Elk Creek. PHOTO BY: FRESHWATER CANADA

Ten says that she would like to see more opportunities to protect other species in Alberta. She notes that she sees programs in the U.S. incentivize the protection of species before their population drops to dangerous numbers. In Canada, restoration work is more reactive.

“There are a lot of other species that are declining that could use our help,” she says. “Once they hit the point of being threatened, then they get attention.”

"A lot of Albertans don't understand the scope and scale of the problem and how it affects them. Even if people don't fish or don't really care about fish, they should still care about the water and where it's coming from."

Climate issues

Funding is not the only issue that restoration groups will face in the future. Lesley Peterson, director of conservation at Freshwater Canada, notes there are many mounting pressures primed to negatively affect restoration efforts. Along with human population growth and economic pressures that will cause increased industrial and recreational use of wild spaces, she cites climate change as a huge driver of habitat loss.

Climate change raises the likelihood of both drought and flooding in watersheds. Increased temperatures in the water can also drive coldwater species like trout further upstream, into dwindling habitat.

Columbia Icefield in Alta (2008). As glaciers shrink from climate change, the flow of downstream creekwater suffers. PHOTO: HARVEY BARRISON / FLICKR

Columbia Icefield in Alta (2008). As glaciers shrink from climate change, the flow of downstream creekwater suffers. PHOTO: HARVEY BARRISON / FLICKR

“A lot of our mid-summer stream flow comes from glaciers,” says Peterson. “So when we lose our glaciers, in the next several decades, that’s going to have impacts on how our rivers function.”

But while climate change poses more difficulties for organizations like Freshwater Canada, restoration efforts can also mitigate the effects that climate change will have on the waterways that flow through our towns and cities.

“As rare weather events become more frequent and/or extreme, we will need to rely on forests and other riparian vegetation to mitigate the flow of water in our rivers and streams,” writes the Alberta Wilderness Association, adding that if streambanks are not maintained, we will see flooding that damages municipal infrastructure.

“We're doing a lot more than just recovering native trout,” says Peteron. “We're actually helping our society and our landscapes adapt to the impacts of climate change.”

Educating Albertans

From designing stickers to hosting conferences and creating educational resources, raising public awareness of the issue is one of the Collaborative's main focuses.

“A lot of Albertans don’t understand the scope and scale of the problem and how it affects them," Peterson says. "Even if people don’t fish or don’t really care about fish, they should still care about the water and where it’s coming from.”

She adds the status of trout as an indicator species should be a reason for Albertans to keep an eye on the unfolding situation.

Cows and Fish Riparian Management Society is another organization involved in the Collaborative, with a focus on promoting knowledge about riparian health. As important to fish habitat as actual waterways, riparian areas include creek and river banks that provide structure and habitat along the sides of streams.

The organization works to connect people with the resources they need to address problems of declining trout populations, having gained their start (and their name) from working with ranchers protecting waterways on their land.

Amy Berlando, provincial riparian specialist at Cows and Fish, looks forward to broadening the scope of the organization by finding new ways to connect to communities in the area. “Not everybody has the same access to our outdoor spaces, not everybody has the same access to information."

She says it’s vital for people to know the importance of these species. “Really, [trout] are the best indicators of watershed health that you can have …It’s really that caring that bridges knowledge into action.”

Freshwater restoration efforts at Trout creek, where the riparian area had been damaged by severe flooding and off-road vehicle use. PHOTO: FRESHWATER CONSERVATION CANADA

Freshwater restoration efforts at Trout creek, where the riparian area had been damaged by severe flooding and off-road vehicle use. PHOTO: FRESHWATER CONSERVATION CANADA

A point of encouragement for Berlando has been seeing the number of people ready to volunteer their time to help address the issue. While Berlando says that a lack of funding makes volunteers indispensable, she also sees the empowering effect that restoration projects have on the volunteers.

“There’s something really powerful about cultivating and planting and putting your efforts into fixing something. And I think that once people do that, they sort of take ownership over that space,”

“In the world we live in today, there are so many things that are negative, that it’s really nice to put your efforts into a place where you feel like you can make a tangible difference. You can come back a year later, a few years later, and you can really see that change.”

About Us

Kelsea Arnett

Kelsea Arnett is a Calgary-based journalist who previously interned at CBC Calgary and The Globe and Mail. She is passionate about covering a range of topics from energy transition to provincial politics.

Alex Janz

Alex Janz bridges her love of environmental science with her extensive skillset in multi-media journalism to engage readers in important topics.

Stephanie Gabriel

Stephanie Gabriel enjoys writing meaningful stories. With experience writing for the Calgary Journal and Humans of Calgary, her hope is to continue doing what she loves.